Coir

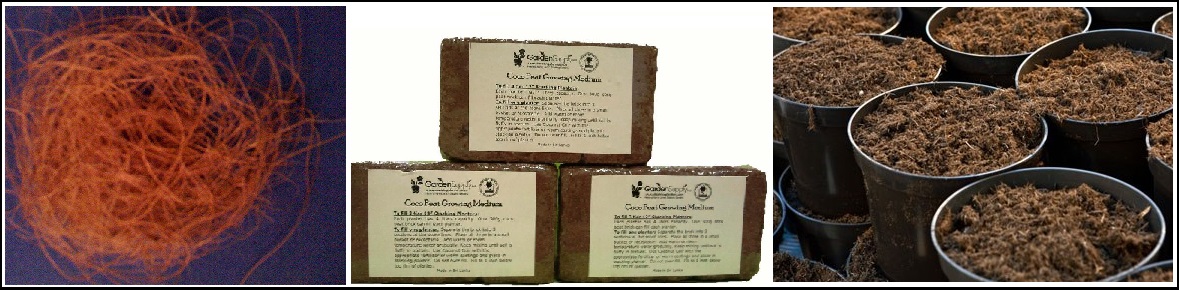

From left to right, a progression of coir fibers; the far left image shows the fibers immediately after harvesting from the coconut. The middle image is a typical packaging form where the fibers have been dramatically compressed and dehydrated into tight dry bricks, suitable for easy transport and long term storage. On the right, the final material after it has been rehydrated.

Coir, also known as coconut fiber, coco-fiber, and coco-peat, is a natural product sold as a soil amendment and hydroponic growing medium. It is made from shredded coconut husks. It is lightweight, easy to work with, does not require special handling or protective clothing, and it can be easily composted. It has been used as a soil conditioner and growing medium for quite awhile, but is not as well known as some other options. It is structurally similar to rockwool and peat moss, featuring long interwoven fibers that form a thick well aerated mat. But the fibers are much larger in diameter than rockwool.

NOTE: Coir should not be confused with peat moss. The two products may have similar texture and appearance, but they have very different sources. Coir, as indicated above, is made entirely, and only, from shredded coconut husks. It is a natural byproduct of the coconut harvesting process, and is considered a renewable product since new crops of coconuts can be regrown repeatedly on the same trees. Peat moss, on the other hand, is a product of typically cold wetlands and swamps, composed of partially dead and some living materials. One debate within the hydroponic and gardening world right now is whether peat moss can truly be called a "sustainable" product, because it it takes hundreds if not thousands of years to develop peat moss bogs. Those bogs are being mined for peat moss at a faster rate than they are being replenished. Also, peat moss has a different chemical profile than coir, being slightly acidic and thus affecting the overall pH micro-environment of the root mass for whatever is planted into it.

Advantages and Disadvantages of Coir

Advantages

are many. Unlike rockwool, the coconut fibers are non-irritating which

makes it positively blissful to work with. It is a naturally occurring fiber,

which many growers favor over manmade materials. Using coconut fiber doesn't add to the

waste stream, but rather diverts it from the waste stream of the coconut milk

processing. It can compress like rockwool, but offers a looser weave that can

be torn apart, fluffed up, or compressed as needed. It offers good water and

air movement. It can be packed tight enough to provide support for all but the

smallest seedlings, yet larger seeds will find easy sprouting conditions. It

can be purchased at many home improvement stores or gardening centers, even

those that have no other hydroponic products in stock. It can be safely

composted after use, or will simply slowly degrade outside. Best of all, it

is sold in many forms, so any given grower can easily find the form which works best for his/her particular circumstances. Bricks ship cheaply and store really well, while loose bags have already been partially rehydrated and even conditioned with additional perlite or other amendments. The expansion rate for bricks is amazing - a single brick will expand to

fill a wheelbarrow. Just add water and wait. One odd feature is that if you

wanted something of a hybrid operation, where plants are started in hydroponic situations then planted out in soil later, this is one of the few

growing media that gracefully allows that transfer.

It does have some disadvantages. While providing a woven texture like rock

wool, it is not so tightly woven so it tends to dry out faster. The natural

fibers will break down faster than just about any other growing medium, so you

will be replacing it at least once a year, possibly more frequently. It is

slightly acidic and it does react with nutrient solutions, so you will have to

monitor pH and adjust accordingly. It will also slowly but regularly shed small

dander-like pieces which can clog irrigation and drainage lines, so filtration

of that material becomes very important very quickly. And finally, thanks to

its relatively fast degradation, it cannot realistically be reused.

One interesting, newly-discovered aspect is that it is not totally inert as we once believed. It has a mild but measurable ability to first absorb potassium when fresh, then that potassium is released later as the coir begins to age and break down into smaller and smaller particles. This update and release of potassium is enough to throw off the nutrient balance and EC for a nutrient solution. Calcium is also partially locked up within the coir, thus requiring slightly higher calcium supplementation for plants. If that imbalance is not addressed, fruiting plants such as tomatoes will start to show specific calcium-deficiency diseases such as blossom end rot. We'll touch more on that aspect of coir in the Nutrients section, which we're still building. In the meantime, some nutrient manufacturers such as General Hydroponics are now offering nutrient solutions specifically designed for use with this growing medium.

Our Experiences

We've used coir extensively for a variety of horticultural reasons, primarily to lighten up heavy potting soil. It does that very nicely, while still retaining moisture like a sponge. We've also used it in hanging plant baskets, which lightens up the basket weight while giving the roots plenty of humid growing room. Additionally, we have occasionally used it as a sprouting medium for seeds, with varying amounts of success. We have lived in a number of different climates, some of which have been very dry and some of which have been very humid. Coir will hold moisture for amazing amounts of time in humid climates, almost too long if the plants are young and not drawing up a lot of water on their own. It can hold moisture long enough that damping off disease becomes an issue. However, it will dry out a little faster in dry climates, so irrigation is still needed for young plants with new root systems. Finally, we have used coir mats as a short-term weed suppression material. It worked well for that purpose, and broke down easily enough after the season's end such that it simply melted into the planting bed soil. Bottom line, we like working with coir because it's relatively clean, easy to handle, not as dusty as some other soil amendments and it's a natural byproduct which would otherwise be sent to landfill.

Where to Find

Coir has become a more common gardening and landscaping item for both

commercial and residential purposes in the last 10 years. Therefore it has

become fairly commonplace in the Gardening section of the home improvement

retailers, as well as with commercial nursery and greenhouse equipment

suppliers.

The first likely source for finding it is as close as your local

hardware store or home improvement center. Many such businesses regularly carry

it, either during the spring growing season or year-round, in either compressed

brick or compressed bale form. Either form can be used as either a soil

amendment or as a pure planting medium.

A second source is the specialty landscaping supplier, nursery supplier or

commercial greenhouse equipment supplier. If you live in a metro area, you will

probably have at least a few such businesses within a few hours' drive. Even

rural areas often have regional supply houses for that area's farming,

greenhouse and nursery businesses. Those supply houses will most often deal

with larger scale commercial clients but they may also work with walkup and

small-scale buyers too.

A third possibility is a wide variety of online retailers. Given how much

the fiber can compress, it can be shipped relatively cost-effectively. So

online retailers can provide competitive pricing even compared to local

suppliers. They may also feature local dealers who offer online pricing with

local pickup. For instance, Gardener's

Supply Company offers coir as

a 12-pack of bricks, at a very competitive price.